The first stock I purchased in my early 20's was a clothing brand that I liked. They had just purchased a manufacturer of skis and snowboards. I purchased the stock because:

- It was familiar to me

- The company made products I liked (clothes, skis & snowboards)

- The stock price was only $7 per share

- I had no idea what the company was worth (Ed. note: at this time it was probably was $3-$4 per share)

So, I purchased a stock at $7 per share that was probably worth $3.50 a share... clearly this purchase was a mistake, and I believe it is a fairly common one. Why would someone make an investment without understanding: the business model, the true value of the company or the competitive landscape? In most cases, the answer is: simply because it is familiar.

It seems to me that we often make similar decisions in life. We might buy a car, a computer or a phone that our friends own because it is familiar to us. We might use an insurance agent, mortgage broker or real estate agent that is a friend. This thought process is fairly logical. You want an insurance agent that you can trust, and it seems easier to trust someone with whom you have a preexisting relationship. The question then becomes: is using your insurance agent friend the best business decision? In some cases it may be, but in many cases, there is probably someone with whom you have no preexisting relationship who can provide better service, rates and coverage. What I'm trying to prove is that buying a familiar stock is sort of like buying insurance from a friend with non-competitive rates... except worse, because there is no social benefit to owning a stock with which you are familiar (and there are often social benefits to doing business with a friend).

Assuming you are investing to increase your long-term wealth, why would you only buy stocks from a handful of companies with which you're familiar, when you could buy thousands of other investments? I imagine it is because the unknown can be scary. In my case, the thought of buying the stock of a company I knew nothing about, in an industry I knew nothing about, was frightening. If I knew next to nothing about the process of buying and selling stocks, I might as well have a little familiarity with the stock I'm purchasing, right?

Let's look into my past purchase to see what we can learn from this mistake. Below is the price chart, with a step-by-step review of my actions and a post-mortem grade for each step.

ZQK stock price from 2008 - early 2011

- I purchased the stock in late 2008 at about $7 per share. Post-mortem grade: F (the stock's true value was somewhere around $3.50 per share)

- In the next three months the stock price went from $7 to about $1 (in three months, the price of my first stock purchase was down 85%). What did I do? I finally started researching the company, I worked to understand the competitive environment and fundamentals. Post-mortem grade: B (I should have done this research initially, but I now had some idea of the true value of my investment)

- Six months later, I decide to purchase more shares at about $1.50 per share. I now had a better understanding of the company and thought the company was worth at least twice the current price. The drop in price allowed me to purchase almost five times as many shares for the same amount as my initial investment. Post-mortem grade: B+ (if I was willing to pay a sufficiently higher price for the stock nine months ago, and the fundamentals of the company haven't changed, I should be happy to invest more money at a discounted price)

- In 2010, I sold all my shares at about $5 per share. Post-mortem grade: B- (I ended up making a nice profit, but much of that was luck. I should have never made the initial purchase.)

Now that we have reviewed my least intelligent stock purchase, let's quickly look at a few more successful purchase decisions. In 2012, I bought Corn Product International (now Ingredion), "a leading global ingredients solutions company," with which I was previously unfamiliar. It had an attractive valuation and strong fundamentals. The more I researched the company, the more I was impressed with their business model. The stock price has more than doubled in four years. Corning, "one of the world’s leading innovators in materials science," is a similar story. I purchased the stock because of attractive business fundamentals (not my familiarity with the company) and I've made a nice return.

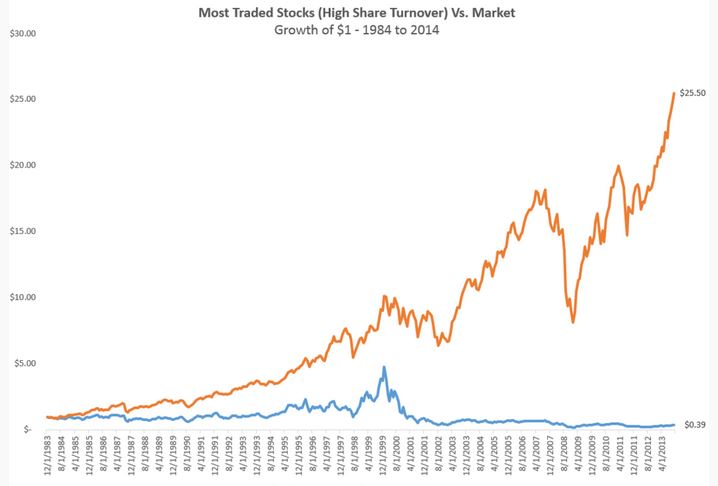

So do the three examples above prove a trend? Absolutely not. Let's review this suggestion that you should be stocks based on fundamentals and not familiarity at a larger scale. Patrick O’Shaughnessy backtested a similar investment strategy recently. In this case, he tested how "popular" stocks (in my eyes a popular stock is a nice proxy for a well known stock) compared to the market. Popular stock are often expensive (high P/E, P/B, etc.) because they are well known. An expensive company has high expectations of future growth. The high expectations are often tough to fulfill, and when the high expectations aren't met the stock price often drops (sometimes significantly). This is shown below, the popular companies (blue line) with high expectations, often failed to meet those expectations and were therefore significantly out performed by the market of all stocks (orange line).

How can you change the process to "stack the deck in your favor"? Instead of buying stocks based on what is familiar to you, buy stocks based on their true value (I will discuss the best stock valuation methods in a future issue). However, as discussed previously, if you're a novice investor owning individual stocks probably isn't a great idea.

Takeaway - Simply purchasing stocks based the fact that they are well known to you has a low probability of success. In today's environment, this might mean that purchasing stock in Dillard's (a "boring" retail store, that you may not shop at, but that has strong fundamentals) has a higher probability of success than Google (the world's most valuable company, which dominates the world's search and mobile phone markets). After all, the most valuable companies in the world (which are familiar to all of us) have significantly under-performed the S&P 500 since 1972.

Valuation metrics and under-priced stocks

US EQUITY VALUATION

Shiller P/E (CAPE Ratio) | As of 012/12/2015

http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/

Mean: 16.63, Median: 16.01, Min: 4.78 (Dec 1920), Max: 44.19 (Dec 1999), Implied future annual return (over 8 years) = 2.9% to -3.2%

Notes on valuation: I look at valuation metrics (like the CAPE ratio shown on the above) to provide some context of how expensive stocks are compared to historical levels. Currently, valuations are above average.

THE DEFENSIVE INVESTOR strategy

Inspired by Benjamin Graham

Defensive Investor Notes: My personal favorite investment strategy uses Benjamin Graham’s (Warren Buffett’s mentor and professor at Columbia Business School) guidance to identify companies, with a strong cash position, low debt, and stable dividends paid over many years that are trading at bargain prices. Similar techniques have yielded annual returns of approximately 18% since 2001.

WORLD’S CHEAPEST STOCK MARKETS

Notes on the world's cheapest stock markets: Investing strategies that buy the world’s most affordable stock markets have proven to be very successful in the past (averaging an annual return of approximately 16% from 1980-2013). For that reason, I keep a close eye on investing opportunities overseas.

The ETF GVAL (http://www.morningstar.com/etfs/arcx/gval/quote.html) leverages this investing strategy for a reasonable fee. Star Capital (http://www.starcapital.de/research/stockmarketvaluation) tracks the world's most undervalued stock markets on a quarterly basis.

the all seasons (risk parity) strategy

Notes on the All Seasons Strategy: I use this strategy for cash management (and to minimize draw-downs). It is intended to reduce volatility without significantly reducing upside. From 1973 - 2012 the max draw-down of this approach was only 14.4% (http://mebfaber.com/2013/07/31/asset-allocation-strategies-2/), yet the compound annual return was a very solid 9.5%... One additional note, this strategy is 70% bonds, which have been in a bull market for 30+ years (which overlaps the backtesting period). In my opinion, it is unlikely to perform as well in the next 30 years as it has in the last 30 years.