Most investors measure themselves against two things: the market and their peers. Most investors are doing it wrong.

The true goal is to save the most money, not the have the best returns. Now, most people think that making the best returns actually creates the most money… they are wrong. The best returns leading to the most money is only true when you invest a lump sum, don’t take money in or out and wait… in life (or business) this basically never happens (you buy a new car, a house, have kids, start a business, etc).

Hopefully, you get the point by now, the person who saves 15% of their income and makes a 5% return will be a lot better off than the person who saves 1% of their income and makes a 15% return. But the investment and financial management professions (along with most investing “news” organizations) get this wrong, they talk about returns rather than a holistic financial picture… and that gives the perception that we should focus on returns. That’s incorrect.

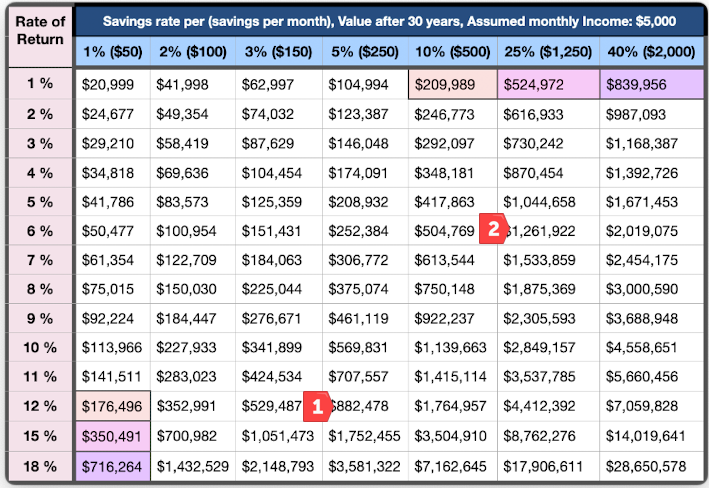

Rene Sellmann (@ReneSellmann) articulates this nicely in the table below. Many people seem to target Point 1 (Saving 5% and planning on a 12% return) rather than Point 2 (Saving 25% and planning on a 6% return). A 12% return over 30 years is challenging and will always be unlikely for someone who isn’t Seth Klarman (and you aren’t), but also, a 5% savings rate means you spend 95% of your income and that means your financial “needs” in retirement are much greater than the person who only spends 75% of their income (the 25% saver in the example below). Increasing your savings rate gives you a bigger nest egg but it also decreases the size of the nest egg you actually need, it’s the super drug of future wealth.

How you save matters much more than your investing returns. We have to ask ourselves if we can change the way we think about investing/savings to painlessly increase our total savings amounts. And the great news is that we can!

American’s largest asset (on average) is their home equity. Do you think that is because real estate is the best-performing investment asset… nope. It’s mostly because of the “forced savings” aspect of a mortgage. People pay their mortgage first and typically pay their mortgage mindlessly (without thought). The lessons from a mortgage teach us a lot about what type of investments can increase our savings rates. They typically have:

First priority for the use of available funds (mortgage, 401k, automated long-term savings plan)

Paid without thought (or automated)

Simple - an investment that can be made without analysis (a tried-and-true investment that you believe in)

A “lock up” period - the funds are hard to get to when you find something new that you “need”

To prove this is true let’s think about the inverse. You have $5000 that you don’t need for anything and you want to invest. You have your eye on some NVDA stock because Jim Cramer won’t shut up about it but you also want a new computer and some new shoes. In that scenario, there is probably an 80% chance that you make a bad bet on an individual stock or blow the money on new toys and only a 20% chance that your “investment” turns into a solid asset in 5 years’ time. That approach to investing rarely increases your savings rate consistently - it’s a problem. Yet you might tell yourself to do it because you are “increasing your investing returns” by spending more time thinking through your investing approach… don’t do that. Make investments using the framework above and move on.

Meb Faber looked at this challenge from a different lens but still came to the same conclusion. He wondered “How much alpha (investing outperformance) do you HAVE to generate to break even on the time spent to achieve it?” He breaks that down in the table below.

The columns on the far right (highlighted in yellow) tell the story here. If your portfolio is worth $500,000 and you make $100,000 per year, you need to outperform the market by 4% per year to make your time invested worthwhile (Meb assumes you spend 8 hours per week on investing research), do you know how hard it is to outperform the market by 4% for one year? Let alone year after year?

There is a clear takeaway here: Use the principles above to get your portfolio value north of 5 million and then we can talk about investing returns.

What are a few simple ways to use the principles above? (note: I don’t care what you use to improve your savings rate, but the following work for me)

Read this: The Wealthy Barber

Use Wealthfront to automate your savings (which uses principles 1, 2, and 3 above)

Use Arrived Homes to buy a piece of single-family rental properties (using principles 3 and 4 above because your investment is illiquid - the typical holding period of each home is 5-7 years)

Obviously, this isn’t investment advice. I don’t expect either of the investment options above to “outperform,” but hopefully you know by now that outperformance doesn’t lead to the biggest pile of money down the road - that requires the best combination of savings rates and investing performance.