The Art of Tracking, with Boyd Varty – [Invest Like the Best, EP.32]

http://investorfieldguide.com/boyd/

Man + Machine, Moats, and Power of the Outside View, w/ Michael Mauboussin [Invest Like the Best, EP.37]

http://investorfieldguide.com/michael/

http://investorfieldguide.com/boyd/

http://investorfieldguide.com/michael/

Agenda:

1. Inversion Thinking

2. Defensive Investor Strategy Performance (up 41.8% in last 12 months)

3. All Seasons Strategy Performance (up 2.5% in last 12 months)

Many good value investors have written about Charlie Munger's use of an approach called inversion thinking. I'd like to briefly discuss inversion thinking in this quarter's newsletter, as well as why I believe that inversion thinking makes a strong case for quantitative investing. Tren Griffin, a Munger biographer, describes this problem-solving approach much more eloquently than I can:

Charlie Munger has adopted an approach to solving problems that is the reverse of the approach that many people use in life. Inversion and thinking backwards are two descriptions of this method. As an illustrative example, one great way to be happy is to avoid things that make you miserable.

Munger even jokes that he wants to know where he will die so he can just not go there. -25iq

I'll attempt to leverage Munger's philosophy to explain how to make wise investments. If you want to make money investing (grow long-term wealth), and you use inversion thinking, start by asking how you would destroy long-term wealth. The next time you decide you would like to destroy your wealth, I would recommend the following:

· Pay high fees and/or commissions

· Buy expensive or speculative assets

· Trade frequently

· Use leverage

· Make emotional decisions about buying or selling assets

If you have read my previous newsletters these suggestions won't come as a surprise (I often recommend the opposite). At this time, I’d like to focus on making emotional decisions. Before we can improve our decision making, we first must understand that we are prone to making poor investing discussions. One typical decision-making deficiency is illustrated in the Greenblatt study. The study identified a group of stocks that outperform the market over time and gave investors two options:

1. To choose when they buy and sell stocks on the list (self-managed)

2. To have a formula determine when to buy and sell stocks on the list (this quantitative approach was described in the study as "professionally managed")

The self-managed account allows clients to choose which stocks to buy and sell from a list of approved Magic Formula stocks. Investors were given guidelines for when to trade the stocks, but were ultimately able to decide when to make those trades. Investors selecting the professionally managed accounts had their trades automated. The firm bought and sold Magic Formula stocks at fixed, preset intervals. During the two year period in Greenblatt's study, both types of account were able to select only from the approved list of Magic Formula stocks.

If investors in the study made rational decisions about the appropriate times to buy and sell stock, I would expect them to outperform the market significantly (because they were given a basket of stocks that outperformed the market).

…What happened? The self-managed accounts, where clients could choose their own stocks from the preapproved list and then exercise discretion about the timing of the trades, slightly underperformed the market. An aggregation of all self-managed accounts for the two-year period showed a cumulative return of 59.4 percent after all expenses, against the 62.7 outperformance of the S&P 500 over the same period. The aggregated professionally managed accounts returned 84.1 percent after all expenses over the same two years, beating the self-managed accounts by almost 25 percent (and the S&P by well over 20 percent) (emphasis mine). For a two-year periods a huge difference. It's especially so since both the self-managed accounts and the professionally managed accounts chose investments from list of stocks and followed the same basic plan. People who self-managed their accounts took a winning system and used their judgment to eliminate all the outperformance and then some (emphasis mine). Greenblatt has a few suggestions about what caused the underperformance, and they are related behavioral biases. - From "Quantitative Value" by Wesley Gary and Tobias Carlisle

The investor's "best judgment" was the difference between outperforming and underperforming the S&P 500. Most investors show similar underperformance in "self-managed" accounts because of emotional decision making when buying and selling stock (causing them to buy high / sell low). We can leverage inversion thinking to solve this problem: if self-management and emotional decision-making are the problem, using a systematic approach is an ideal solution. Depending on your investing approach, implementation of a systematic or quantitative approach might vary:

1. For an index investor – it probably means buying at predefined intervals (every two-weeks, monthly, etc.)

2. For a disciplined value investor – it likely means buying when a stock is significantly below fair value and selling when the stock reaches fair value

3. For a less disciplined value investor – it likely means buying stocks that are significantly below fair value and selling after a defined period of time (one year, three years, etc.)

Is your "best judgment" the cause behind your investment’s underperformance? It's worth some thought. If so, consider adding a quantitative element to your investing approach.

If you are interested in additional reading on the subject check out the following links: on Munger; on Quantitative Investing.

My Benjamin Graham inspired fund has outperformed the S&P 500.

In the last 12 months, it is up 43.2% (through December 21, 2016).

Defensive Investor Notes: My personal favorite investment strategy uses Benjamin Graham’s (Warren Buffett’s mentor and professor at Columbia Business School) guidance to identify companies with a strong cash position, low debt, and stable dividends paid over many years that are trading at bargain prices. Similar techniques have yielded annual returns of approximately 18% since 2001.

My more conservative "All Seasons" inspired fund is up 2.5% in the last 12 months (through December, 21 2016).

Notes on the All Seasons Strategy: I use this strategy for cash management (and to minimize draw-downs). It is intended to reduce volatility without significantly reducing upside. From 1973 - 2012 the max draw-down of this approach was only 14.4% (http://mebfaber.com/2013/07/31/asset-allocation-strategies-2/), yet the compound annual return was a very solid 9.5%. One additional note- this strategy is 70% bonds, which have been in a bull market for 30+ years (this overlaps with the back-testing period). In my opinion, it is unlikely to perform as well in the next 30 years as it has in the last 30 years.

The first stock I purchased in my early 20's was a clothing brand that I liked. They had just purchased a manufacturer of skis and snowboards. I purchased the stock because:

So, I purchased a stock at $7 per share that was probably worth $3.50 a share... clearly this purchase was a mistake, and I believe it is a fairly common one. Why would someone make an investment without understanding: the business model, the true value of the company or the competitive landscape? In most cases, the answer is: simply because it is familiar.

It seems to me that we often make similar decisions in life. We might buy a car, a computer or a phone that our friends own because it is familiar to us. We might use an insurance agent, mortgage broker or real estate agent that is a friend. This thought process is fairly logical. You want an insurance agent that you can trust, and it seems easier to trust someone with whom you have a preexisting relationship. The question then becomes: is using your insurance agent friend the best business decision? In some cases it may be, but in many cases, there is probably someone with whom you have no preexisting relationship who can provide better service, rates and coverage. What I'm trying to prove is that buying a familiar stock is sort of like buying insurance from a friend with non-competitive rates... except worse, because there is no social benefit to owning a stock with which you are familiar (and there are often social benefits to doing business with a friend).

Assuming you are investing to increase your long-term wealth, why would you only buy stocks from a handful of companies with which you're familiar, when you could buy thousands of other investments? I imagine it is because the unknown can be scary. In my case, the thought of buying the stock of a company I knew nothing about, in an industry I knew nothing about, was frightening. If I knew next to nothing about the process of buying and selling stocks, I might as well have a little familiarity with the stock I'm purchasing, right?

Let's look into my past purchase to see what we can learn from this mistake. Below is the price chart, with a step-by-step review of my actions and a post-mortem grade for each step.

ZQK stock price from 2008 - early 2011

Now that we have reviewed my least intelligent stock purchase, let's quickly look at a few more successful purchase decisions. In 2012, I bought Corn Product International (now Ingredion), "a leading global ingredients solutions company," with which I was previously unfamiliar. It had an attractive valuation and strong fundamentals. The more I researched the company, the more I was impressed with their business model. The stock price has more than doubled in four years. Corning, "one of the world’s leading innovators in materials science," is a similar story. I purchased the stock because of attractive business fundamentals (not my familiarity with the company) and I've made a nice return.

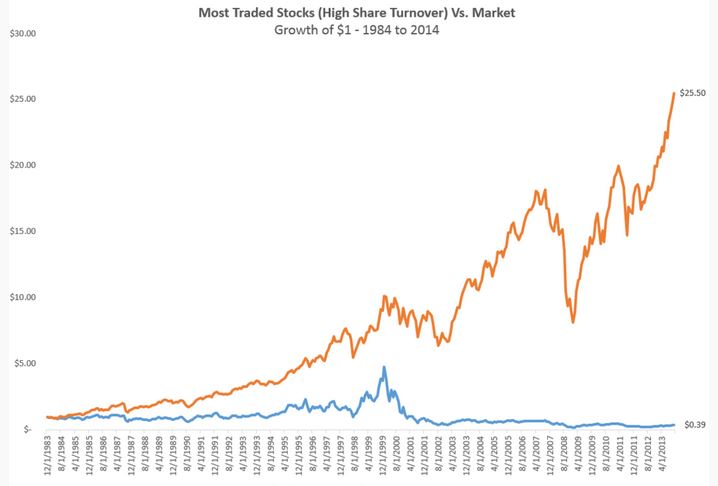

So do the three examples above prove a trend? Absolutely not. Let's review this suggestion that you should be stocks based on fundamentals and not familiarity at a larger scale. Patrick O’Shaughnessy backtested a similar investment strategy recently. In this case, he tested how "popular" stocks (in my eyes a popular stock is a nice proxy for a well known stock) compared to the market. Popular stock are often expensive (high P/E, P/B, etc.) because they are well known. An expensive company has high expectations of future growth. The high expectations are often tough to fulfill, and when the high expectations aren't met the stock price often drops (sometimes significantly). This is shown below, the popular companies (blue line) with high expectations, often failed to meet those expectations and were therefore significantly out performed by the market of all stocks (orange line).

How can you change the process to "stack the deck in your favor"? Instead of buying stocks based on what is familiar to you, buy stocks based on their true value (I will discuss the best stock valuation methods in a future issue). However, as discussed previously, if you're a novice investor owning individual stocks probably isn't a great idea.

Takeaway - Simply purchasing stocks based the fact that they are well known to you has a low probability of success. In today's environment, this might mean that purchasing stock in Dillard's (a "boring" retail store, that you may not shop at, but that has strong fundamentals) has a higher probability of success than Google (the world's most valuable company, which dominates the world's search and mobile phone markets). After all, the most valuable companies in the world (which are familiar to all of us) have significantly under-performed the S&P 500 since 1972.

Shiller P/E (CAPE Ratio) | As of 012/12/2015

http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/

Mean: 16.63, Median: 16.01, Min: 4.78 (Dec 1920), Max: 44.19 (Dec 1999), Implied future annual return (over 8 years) = 2.9% to -3.2%

Notes on valuation: I look at valuation metrics (like the CAPE ratio shown on the above) to provide some context of how expensive stocks are compared to historical levels. Currently, valuations are above average.

Inspired by Benjamin Graham

Defensive Investor Notes: My personal favorite investment strategy uses Benjamin Graham’s (Warren Buffett’s mentor and professor at Columbia Business School) guidance to identify companies, with a strong cash position, low debt, and stable dividends paid over many years that are trading at bargain prices. Similar techniques have yielded annual returns of approximately 18% since 2001.

Notes on the world's cheapest stock markets: Investing strategies that buy the world’s most affordable stock markets have proven to be very successful in the past (averaging an annual return of approximately 16% from 1980-2013). For that reason, I keep a close eye on investing opportunities overseas.

The ETF GVAL (http://www.morningstar.com/etfs/arcx/gval/quote.html) leverages this investing strategy for a reasonable fee. Star Capital (http://www.starcapital.de/research/stockmarketvaluation) tracks the world's most undervalued stock markets on a quarterly basis.

Notes on the All Seasons Strategy: I use this strategy for cash management (and to minimize draw-downs). It is intended to reduce volatility without significantly reducing upside. From 1973 - 2012 the max draw-down of this approach was only 14.4% (http://mebfaber.com/2013/07/31/asset-allocation-strategies-2/), yet the compound annual return was a very solid 9.5%... One additional note, this strategy is 70% bonds, which have been in a bull market for 30+ years (which overlaps the backtesting period). In my opinion, it is unlikely to perform as well in the next 30 years as it has in the last 30 years.

I've recently added performance tracking to the website for two of my favorite investing strategies.

From July 22, 2015 to June 9, 2016 the Benjamin Graham Defensive Investor Strategy was up 21.9%. I rebalanced the strategy on June 9, 2016; there are now six stocks that meet the criteria.

The All Season Fund is designed to minimize draw-downs. It has also performed well recently.

I was reviewing asset allocation with a friend recently... Vanguard does a great job of explaining the pros and cons of different asset mixes here.

Fidelity has a nice write-up on why you should consider increasing your exposure to international stocks - https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/investing-ideas/more-international-stock

Wesley Gray did a great "Academic Research Recap" on articles that have changed his mind/approach over the years. It's the best thing I've read in months. Go read it. Below is one quote from the article.

"Essentially, long duration investment opportunities, while attractive in a perfectly rational world with full information, are not necessarily attractive if they make a manager look bad in the short-run, and the investors pull all their money when the manager performs poorly relative to a benchmark in the short-run."

Noah Smith has a nice article in Bloomberg, on adviser fees. Quotes and the link are below:

"Now, with the industry-standard 1 percent management fee, you pay a full 25 percent of your life’s savings to your money manager. It’s much higher than before, and because since you’re earning a higher return, the fee gets sliced off of a bigger and bigger salami.

Think about that for a moment. What else would you spend so much money on? Your house, and that’s it. After your house, asset management will be the most expensive thing you ever buy."

"If your wealth manager helps you take more risk and make fewer bad choices, and if this boosts your average lifetime return by 2 percent a year, then he has more than earned his 1 percent fee."

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2016-04-11/those-tiny-fees-make-your-financial-adviser-rich

Morgan Housel has another excellent column on the common volatility of stocks, including the best performing stocks in the past 20 years. He includes the classic Munger quote:

"This is the third time that Warren [Buffett] and I have seen our holdings in Berkshire Hathaway go down, top tick to bottom tick, by 50%. I think it's in the nature of long-term shareholding that the normal vicissitudes in markets means that the long-term holder has the quoted value of his stocks go down by, say, 50%.

In fact, you can argue that if you're not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century you're not fit to be a common shareholder, and you deserve the mediocre result you're going to get compared to the people who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations."

Read the entire article here: http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2016/02/09/the-agony-of-high-returns.aspx

Some nice back-testing on the ideal retirement withdraw strategies... http://time.com/money/4166109/best-retirement-withdrawal-strategies/

After the Q2 Newsletter, I answered a good number of general questions on investing and retirement planning. Therefore, I've decided briefly discuss some basic investment guidance for the "average" investor (or novice investor). Are you a novice investor? Probably. Here is a quick test. Do you know:

If you don't know the answers to the majority of those questions it is safe to say that you are a novice investor (which isn't bad or uncommon). It's estimated that a large majority of all investors fall into this category.

So, assuming you are a non-expert investor, what are some simple guidelines to follow to help you achieve future goals? I'll suggest a few:

This is very simple concept. If you are looking to build wealth to achieve future goals you have to spend less than you make. If you're investing for retirement, most experts recommend saving between 10% and 15% of your salary. If you currently save much less than 10% of your salary, try small increases over many years to get to 15% or more. This principle called "save more tomorrow" has been shown by behavioral economists to increase savings rates significantly over time by reducing drastic lifestyle changes that come with a significant change in savings rates. Here is a quick example: say you currently save 6% of your salary and you get a 2% raise each year. When you get your next raise, increase your savings rate to 7%, do the same the next year and the year after that. In nine years, you will have increased you savings rate to 15% without changing your lifestyle significantly. Additional reading on the save more tomorrow study is available here.

In 1973, a US postage stamp cost 8 cents, but in 2012 a stamp cost 45 cents (and in 2015 a stamp costs 49 cents). This means that if you had $100 in 1973 you could have purchased 1,250 stamps. Yet in 2012, $100 only purchases 222 stamps (your purchasing power declined by over 5.5 times in the 39 years). This is important because it illustrates just how costly it can be to not to invest. If you invested that $100 in a 60/40 combo of stocks and bonds in 1973, it would have been worth $3,773 in 2012... and would allow you to buy 8,384 stamps (increased purchasing power of more than 6 times what it was in 1973). While sticking $100 under your mattress, would obviously leave you with $100 today. What seems "safe" in the short-term is extremely costly in the long-term. Focusing on the long-term allows you to increase your purchasing power over time.

The trade-off for the greater return provided by investing in stocks is volatility. Your investment could be worth $100 one day, $102 another and $93 a month later. Owning stocks is equivalent to owning a piece of a company, and some companies will fail. This is why the average investor should diversify, owning one company or one asset creates unnecessary risk. My recommendation for the average investor is simple: own multiple assets types. Start with stocks and bonds.

The appropriate percentage of each is less important than you may think. Back-testing of nine different (frequently recommended) asset allocation strategies shows similar returns over 39 years (1973 - 2012). Additional details here.

Source: Meb Faber, CAGR stands for compound annual growth rate, MaxDD is maximum draw down

If you're thinking this seems too complicated, you are in luck. There are excellent investment options for you, with solid well researched and back-tested strategies that you can purchase for very reasonable fees. Investing in or working with one of the providers below we almost certainly outperform 90% of your peers over long periods of time (10+ years). Recommendations include:

This is also very simple, but might be the most important thing with which the average investor should be concerned:

Source: Vanguard

If you minimize fees, you make $93,923 more money with no additional work. The best way to do this is to buy funds from Vanguard, because Vanguard has a unique ownership structure - "The company's profits are used to return dividends to its investors and to lower management fees." Vanguard funds almost always have the lowest fees available in the market.

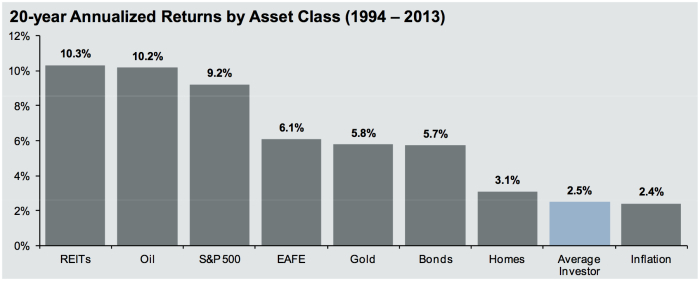

Tests show that it is twice as painful to lose a dollar as it is joyful to gain a dollar. When the a new pair of Nikes are on sale for 40% off, you are much more likely to buy them (or at least I am). Yet, when your investments drop by 40% many people sell. The average investor return from 1994 to 2013 was 2.5%. This is because too many investors sell when their investments drop in value and buy investments near their peak (sell low / big high).

Source: JP Morgan Guide to the Markets Q4 2014 using DALBAR data ending in December 2013.

An investor return of 2.5% is much worse than it should be, but not necessarily surprising. Our brains are wired for hunting and gathering, rather than investing in stocks. There an easy way to improve your investing behavior, by rebalancing your investments. The automatic portfolios suggested above correct for your human investing weakness by rebalancing annually. You should too. Rebalancing simply forces you to buy stocks or bonds when the prices have gone down (and they are a deal). Example: If you started the year with a 50/50 mix of stocks and bonds and stocks performed poorly at year end you might have a 45/55 mix of stocks and bonds. At the beginning of the year you would sell some bonds and buy some stocks to get back to a 50/50 mix. This forces to to buy more of the undervalued asset and significantly improves returns overtime.

Shiller P/E (CAPE Ratio) | As of 012/12/2015

Mean: 16.63, Median: 16.01, Min: 4.78 (Dec 1920), Max: 44.19 (Dec 1999), Implied future annual return (over 8 years) = 2.9% to -3.2%

Notes on valuation: I look at valuation metrics (like the CAPE ratio shown on the above) to provide some context of how expensive stocks are compared to historical levels. Currently, valuations are above average.

Inspired by Benjamin Graham | As of 12/12/2015

Defensive Investor Notes: My personal favorite investment strategy uses Benjamin Graham’s (Warren Buffett’s mentor and professor at Columbia Business School) guidance to identify companies, with a strong cash position, low debt, and stable dividends paid over many years that are trading at bargain prices. Similar techniques have yielded annual returns of approximately 18% since 2001.

Five cheapest stock markets | As of 10/30/2015

Source: Star Capital

Not surprisingly, the world’s cheapest stock markets are often “cheap” for a reason (this approach isn’t for everyone). Countries like Russia have significant challenges, but often represent extraordinary value. For that reason, diversification is critical for long-term success.

Notes on the world's cheapest stock markets: Investing strategies that buy the world’s most affordable stock markets have proven to be very successful in the past (averaging an annual return of approximately 16% from 1980-2013). For that reason, I keep a close eye on investing opportunities overseas.